A Design Brief for the Planet

Review of The Stack by Benjamin B. Bratton (MIT, 2016)

Book Review

Unpublished

May 2016

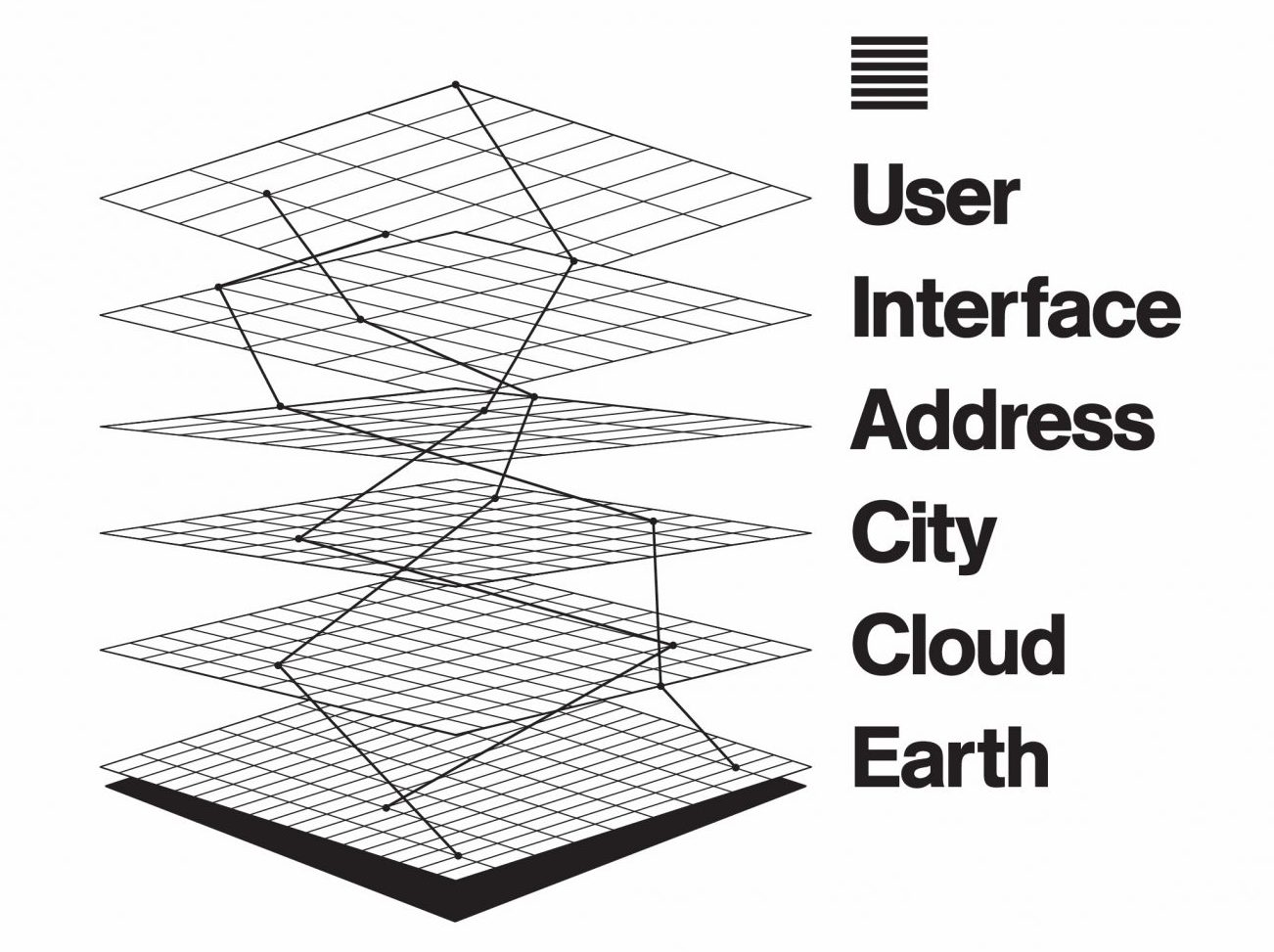

Diagram of the Stack by Metahaven (2016)

A new Leviathan has risen. It has wrapped itself around the entire planet, spreading its fibre-optic tentacles through the depth of ocean beds, voraciously feeding on rare-earth metals and dwindling energy reserves, regurgitating trillions of interconnected smart things that mediate nearly every inch, second, and calorie of humans’ lives. Stretching from the Earth’s crust to the outer atmosphere, the “Stack” is a thick totality, an “accidental megastructure” resulting from the assemblage of all material objects, agents, and processes involved in the current condition of “planetary-scale computation”.

Such is the hypothesis put forward in Benjamin H. Bratton’s new book “The Stack: On Software and Sovereignty” (MIT Press, 2016). More specifically, the conceptual figure of the Stack is posited as a means to explore the new architecture of governance that results from the extensive underpinning of the world(s) we inhabit by computational infrastructure. Acknowledging the gap between a still predominantly flat theory of political geography – as encapsulated in Carl Schmitt’s idea of the “nomos of the Earth” – and the increasingly thick overlap of power structures in operation around our planet, the book sets out to produce an updated map of geopolitical sovereignty after Google.

Central to the argument developed in the book is the notion of “platform”: an organizational apparatus that provides standard protocols of exchange between users, and capitalises on the “decentralised and undetermined interactions” that it thereby supports. With reference to the planetary ubiquity of some California-based tech giants, the author speaks of the emergence of “platform sovereignties”, the material infrastructures of which literally dig under, orbit above, and cut through the bounded surfaces of nation-states. Nonetheless, “The Stack” is all but another funeral march for the state. On the contrary, it is the very grinding of platform against state sovereignty, as well as their reciprocal hybridisation and topological interlocking, which is analysed from the vantage point of each of the proposed layers of the Stack: Earth, Cloud, City, Address, Interface, and User. As new circuits of power are negotiated that pass through human and non-human entities alike, another key theme examined throughout the book is that of the displacement of the centre of gravity of political subjectivity from the individual human citizen towards a post-anthropocentric horizon.

“The Stack” is a book of great ambition and imaginative power. Most remarkable is the way it makes use of informed speculation as a discursive engine, which keeps propelling the argument into uncharted theoretical territory. As a result, the book teems with an alien conceptual fauna – one that proves necessary to work one’s way through the most unsettling idea it puts forward: that of “computation as governance”.

TOTALITY AND SCALE

Having just been through half a century of “post-isms” of all kinds, readers will be excused for showing a certain a priori scepticism in front of any theory of totality. As a consequence, they may well be put off by “The Stack” which, from its very first pages, sets out to describe a “technological totality as the armature of the social itself”. It is nonetheless worth bearing with it. The tour de force of this book is to make the question of the ontological reality of the proposed figure of the Stack simply irrelevant. Once posited and imagined at the right

scale – the planetary one, which is in fact no longer a scale but a rationality – it “serves as a conceptual-technical structure to think with and against as we compose what does emerge.” The epistemological value takes precedence over the ontological one; it is about what the Stack does, not what it is.

What does the figure of the Stack do? It establishes a continuous field, co-extensive with the planet itself, within which particular computational processes can be tracked from the molecular to the atmospheric level and back, without breaking them down into a priori spatial frames where they would appear either too tiny, or too grossly cropped. From daily gestures such as asking a smartphone for the fastest route home, to the modelling of the appropriate response to the next expectable hurricane, through the fluctuation of a city’s housing market or the execution of a signature drone strike, there is no such thing as a particular scale at which the defining events and processes of our time are taking place and can be optimally confronted – no more than there is a local realm distinct from a global one. All we have is the planetary interweaving of localised occurrences, describing increasingly nonlinear causal patterns. In this becoming-weather of our world, computational infrastructure plays a crucial role: striating the surface of the earth and returning a smooth space for data currents to flow ever-faster, while new fault lines emerge over the effective control of this information.

While positing a totality as big as the planet is necessary to apprehend the tectonic shifts brought about by planetary-scale computation in the configuration of geopolitical governance, it is also not enough. Indeed, this would simply mean getting rid of any organizational structure, removing the possibility of cutting through the planet’s whole – which remains overwhelmingly vast and dense, and as such doesn’t lend itself to direct apprehension. Getting rid of pre-given scalar categories to organise inquiries and responses to contemporary problems is most often a good idea, but one should be wary not to throw the baby – the possibility of analytical thinking – out with an epistemologically dirty bathwater. As indicated by its etymology – as a ladder or flight of steps – the notion of scale is intrinsically plural: a fundamental tool of analysis, it allows the breaking down of an issue or an answer into correlated parts, the resulting parts being held together by their particular, ‘scalar’ correlation. Today, while the metric of distance employed to define geographical scales may no longer be appropriate to account for meaningful relations in our planetary condition, the solution is not to get rid of any metric, of any organizational principle enabling to breakdown a problem into correlated parts. On the contrary, a key challenge today is to imagine new ways of measuring our planet, and accordingly, to partition the planetary processes and phenomena into frames we can apprehend and act upon in meaningful ways.

In this regard, the layers of the Stack already formulate a response to this challenge. They breakdown an original planetary totality into correlated subsets, the nature of which is not scalar but operational. Each layer corresponds to a particular domain of operation in the computing meta-machine that the book imagines. Any single computational request – take the example of sending an email to someone – will traverse all layers of the Stack, often back and forth several times. But regardless of the diversity of machinic entities that compose each layer, these are brought together by the very nature of the operation they perform at that particular layer. For example, the Earth layer is primarily concerned with the extraction of the matter and energy required by computation, as well as their distribution across a planetary grid. At the other end, the User layer encompasses everything that takes part in the process of individuation of the subjects of computation, the outputs of which increasingly venture below, above, and beyond the level of the individual human. The key advantage of this particular subdivision of the totality initially posited over a typical scalar one is that layers bring things together on the basis of their operational role, rather that their mere physical proximity. As such the Stack is as much an abstract machine as it is an analytical and design tool: it comes with a lens set that attempts to keep problems in focus as they travel, splinter and cluster across an ever thickening technosphere.

Only some empirical work of analysis and design with the proposed categories can tell if the layers of the Stack, as they have been defined here in theory, are valid and useful ones; or, whether a different subdivision, a different primary composition, is necessary in order to truly grasp, and intervene into, the reconfiguration of power structures brought about by the phenomenon of planetary computation. Regardless, the epistemological manoeuvre deployed by the book – positing an interconnected totality and defining its components based on the particular role they respectively play – has value much beyond the topic of computation. At any rate, it calls for analogous explorations from different entry points into the planetary totality, from climate change to warfare or debt.

As it diagrams a particular articulation of Earth and subjects, “The Stack” is also a direct response to the problem of “cognitive mapping” raised by Frederic Jameson; namely, that of the crippling mismatch between the individual subject’s phenomenological experience and the truth of its “structural coordinates” in the world. In his well-known essay, after mocking the default refusal of any totalising theory that is characteristic of post-modernism, Jameson goes on to illustrate the political stake of the problem of cognitive mapping by quoting (not without a certain irony) Team 10 architect Aldo Van Eyck: “But if society has no form, how can architects build its counter-form?”. Reviving a long-gone tradition of visionary if naive theoretical ambition, “The Stack” does exactly that: it gives form to a society as a whole – a planetary entanglement of humans, algorithms, minerals, and LOLcats. Given the West’s long-term condition of political fatigue, it may be time to restart praising such efforts, rather than decrying them for their lack of de rigueur theoretical particularity.

DESIGN AND USER

The book dives deeper into its own hubris: not only does it take on the challenge of drawing a new and up-to-date geopolitical world map, but it does so with a view to make the whole planet available for (re-)design. The author himself presents it as “a book of design theory.” By that, one should not understand a manual of political theory for designers and architects; what is at stake is not the translation of a discourse about governance into one of design. Rather, design is recognised here as the key problem – as well as the primary mode of actualisation – of the new configurations of power that the book attempts to grasp.

In this regard, a close companion to “The Stack” is Keller Easterling’s “Extrastatecraft: The Power of Infrastructure Space” (Verso, 2014). Arguably, once brought together under the same lens, these two works open up an important new chapter in the examination of the problem of agency which has haunted the architectural discourse since the early seventies, offering a new line of flight out of the dialectic of autonomy and contingency. Following that very line, it is no longer a question of assessing whether architecture’s ambitions are aligned with the discourse of power; and if they aren’t, debating whether architects should withdraw into an introspective yet righteous disciplinary practice, or to engage and negotiate with murky urban agendas. Here we are venturing beyond the political “as a discursive realm transcendent of the physical urban polis itself” – a framework within which architecture was expected to merely symbolize, manifest, or actualise a political project existing somewhere else. The sovereignty of platforms, the power of infrastructure space, are essentially immanent to their technical organisation, to their spatial configuration, to their “disposition”. As such, design is to such forms of power what rhetoric is to forum-based politics: a crucial means of bending opinions, of activating policies, of doing politics. Another way of expressing the notion of “computation as governance” is to speak about the conflation of “architectural, computational, and political” programs into one, which is nowhere more manifest than in the operation of platforms. Increasingly, governance is what we get as an attachment to service-provision.

As design moves to the forefront of this new political geography in the making, it brings alongside with it an unescapable question: design for whom? Who is the target user? Far from reducing platforms to their coercive effects, in several occasions the book highlights their emancipatory potential; namely, how platforms may help users to circumvent policies of exclusion and denial or rights that states implement against them. Taking the example of illegalised migrants crossing into the US helped by GPS devices they purchased at a WalMart in Mexico, the idea that platforms grant users access to their infrastructure regardless of their status as (non-)citizen in the eyes of a state is particularly telling about the on-going reconfiguration of power relations that this overlapping of sovereignties is generating. On the one hand, everyone is increasingly a subject of multiple sovereignties and jurisdictions simultaneously, which, at times, opens up the possibility of playing one against the other in order to pursue one’s own goals. But more importantly, the hybridisation of states and platforms profoundly transforms the status of the user-subject – the latter no longer being attached to a given individual human, but rather to a mere position within a system, a data shadow, that can interchangeably be occupied by a crowd or only a segment of an individual entity. Deleuze’s “dividuals” are pullulating. The author is right to quickly shift the question of “design for whom?”, to one of “design of whom?”. As we entrust platforms with the management and mediation of ever more facets of our lives, the particular architecture of each of those platforms ends up, by extension, delineating the contours of our own contingent subjectivity. What is more, the universally inclusive character of platforms – most often a mere manifestation of their ruthlessly expansionist agenda – means that we, as in us humans, are just one of the different substances that new composite target users are made of. And perhaps already a secondary one.

Rather than warning us against it, the author appears to welcome the emergence of not- quite-human platform users and their gain of importance as valid subjects of planetary governance. After all, isn’t the excessive anthropocentrism of human societies largely responsible for their messing up of the whole planet’s ecosystem? This is where “The Stack”’s most daring proposition is articulated: a call for a form of design – and consequently a form of politics – that doesn’t start nor end with the individual human as its subject. Reminding of Donna Haraway’s invocation of the “cyborg” as a potential figure of emancipatory politics to be constructed, or Sadie Plant’s call to move from “a question of liberation” of women and men to one of “engineering”, the kind of design invoked in the book is one that addresses its subjects and objects in a single movement. Design as an equation in two variables.

As inspiring as this idea may be, the book does not expand much on its concrete implications and possible applications. The question of the imagination and design of new valid subjects for the planet can only be a politically pregnant one when posed alongside the companion question: “design by whom?”. On this critical point, the book would have benefitted from a more grounded discussion on how platforms are to be appropriated and inflected, how they can be shaped by users’ desires, how new users and subjects are to be shaped in return, and who will actually design the Stack to come. The West may well be undergoing another “Copernican trauma” with regard to the dislocation of the individual human subject from the centre of the computational universe. But the impending climate catastrophe also means that there is little time to muse over the fabrication of the post-human(ist) subject of the future; unless we – the privileged users of the very technology that largely contributes to climatic deregulation – declare that, as we endeavour to re-design ourselves and our world as hybrids, we do not mind doing without the radical subjective alterity of the indigenous communities in the front lines of climate change, which are being wiped out at a faster rate than the Western capacity to learn from their already hybrid cosmologies and subjectivities. No doubt that we need the far-reaching gaze of speculation to push the limits of the possible today; but speculative efforts won’t be of much help if they don’t consolidate in a theory of design and politics capable of supporting action in the present – within and against its emergencies.